Our beautiful planet is shared by many diverse people who are working hard to make it a better place for future generations! This National Hispanic Heritage Month, we wanted to highlight a few Hispanic Americans who are making a difference in local and global conservation.

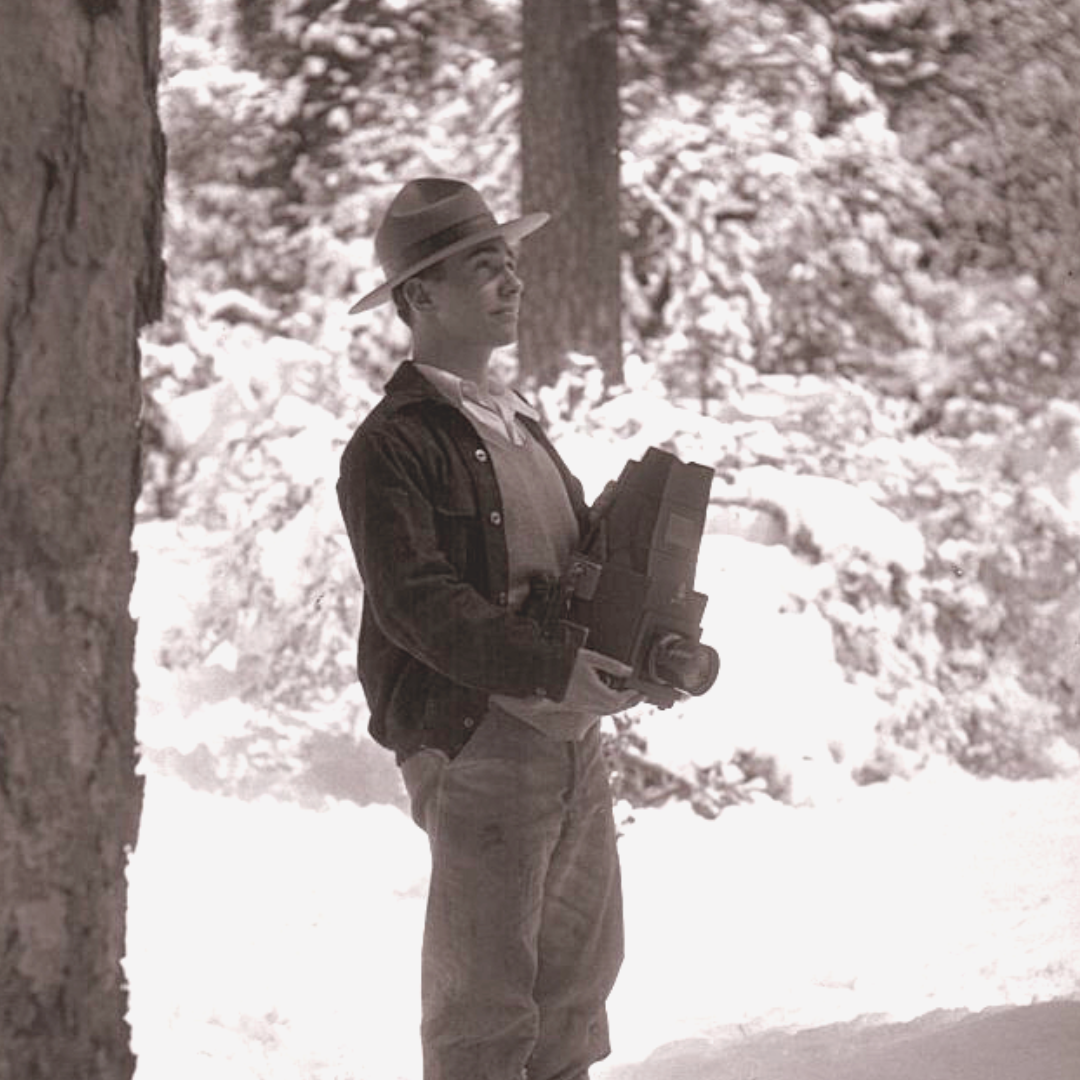

George Wright

George Wright, a San Franciscan of Salvadorian descent, was born in 1904. As a teenager, Wright was an avid hiker, Boy Scout instructor and the President of the Audobon Club. In college he went on to major in forestry at the University of California, Berkeley.

George Wright, a San Franciscan of Salvadorian descent, was born in 1904. As a teenager, Wright was an avid hiker, Boy Scout instructor and the President of the Audobon Club. In college he went on to major in forestry at the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1927, Wright was hired by the Yosemite National Park as an assistant park naturalist, where he taught field classes and wrote for Yosemite Nature Notes. Wright established and personally funded the National Parks Service’s first wildlife biology plan where he studied and advocated against the frequent killings of predators in several national parks across the country. Wright documented the loss of coyotes, eagles, badgers and more, and made the case for the National Parks to institute a wildlife division. In 1931, the National Parks Service was finally able to designate a wildlife budget and two years later they established their first Wildlife Division. Wright was named the first division chief, later becoming the head of the National Resources Board. Under his leadership, parks across the nation began to survey wildlife populations and identify threats. As one of the first and only Latino staff for the Park Service, Wright was a pioneer in celebrating diversity in protecting wildlife and wild places.

Sadly, in 1936 while traveling from newly established Big Bend National Park in Texas, Wright was killed in a car crash. He is honored with mountains named after him in both Denali National Park and Big Bend National Park. In 1980, the George Wright Society was founded in his honor to continue his legacy of conservation.

Photo of George Wright in Yosemite National Park, courtesy of georgewrightsociety.org.

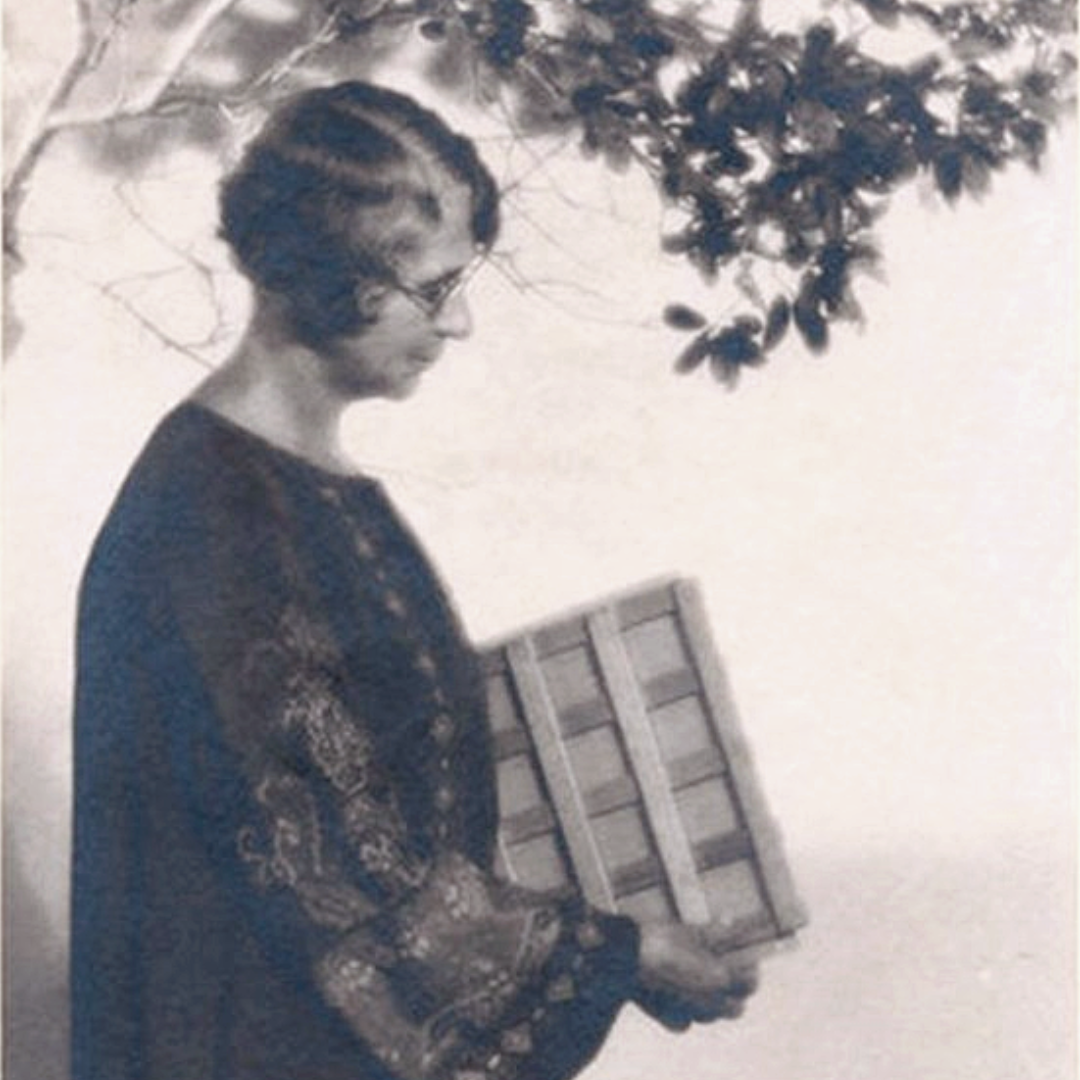

Ynes Mexia

Ynes Mexia was the first female Mexican American botanist, and she didn’t start her career until she was 55! Mexia was born in Washington D.C. in 1870. As a child she attended multiple schools in the U.S., frequently moving until she moved back to Mexico to work on her father's ranch as a young adult. When her father died in 1896, Mexia took over the management of the ranch. Her first husband died a few years after they were married, and she divorced her second husband after he bankrupted her family. Due to her turbulent life, Mexia suffered a mental break in 1909 and traveled to San Francisco to seek treatment where she discovered her love for the environment.

Ynes Mexia was the first female Mexican American botanist, and she didn’t start her career until she was 55! Mexia was born in Washington D.C. in 1870. As a child she attended multiple schools in the U.S., frequently moving until she moved back to Mexico to work on her father's ranch as a young adult. When her father died in 1896, Mexia took over the management of the ranch. Her first husband died a few years after they were married, and she divorced her second husband after he bankrupted her family. Due to her turbulent life, Mexia suffered a mental break in 1909 and traveled to San Francisco to seek treatment where she discovered her love for the environment.

Mexia joined the Sierra Club and Save the Redwoods League, where she became invested in the national park conservation movement, especially the preservation of redwood trees. In 1921 at the age of 51, Mexia’s passion inspired her to attend UC Berkeley and study botany. Through her studies, Mexia was encouraged to collect and categorize plants and conduct field work. She took her first group plant collecting trip in 1925, and at 56 years old she began a 13-year career in botany. Throughout her lifetime, Mexia collected over 145,000 plant specimens throughout the Americas. Usually, she chose to travel alone or with one or two Indigenous guides. She strongly advocated for the rights of Indigenous people in the areas where she collected. Mexia discovered and categorized over 500 plant species, more than 50 of which were named after her today. She was even the first botanist to collect plants in the area now known as the Denali National Park.

Later in her career, Mexia became a prominent lecturer and writer. Unfortunately, in 1938, Mexia was diagnosed with lung cancer and died shortly after at age 68. Most of her estate was left to the Save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club. Today, researchers still use the collections of plants compiled by Mexia, and many of her original specimens can still be seen on display in museums and universities.

Photo of Ynes Mexia with her plant dryer, courtesy of University of California Berkeley.

Miguel Ordeñana

Miguel Ordeñana is the Senior Manager of Community Science at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Ordeñana grew up in California near Griffith Park, where he first found his passion for wildlife. Though he did not come from a family of biologists, he was inspired by the nature around him and the work of leading experts like Jane Goodall. In college, Ordeñana attended the University of Southern California to pursue a degree in Environmental Studies, later obtaining a M.S. in Ecology from UC Davis.

Miguel Ordeñana is the Senior Manager of Community Science at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Ordeñana grew up in California near Griffith Park, where he first found his passion for wildlife. Though he did not come from a family of biologists, he was inspired by the nature around him and the work of leading experts like Jane Goodall. In college, Ordeñana attended the University of Southern California to pursue a degree in Environmental Studies, later obtaining a M.S. in Ecology from UC Davis.

As an environmental educator and a wildlife biologist, Ordeñana conducts urban mammal research in L.A. and surrounding areas. He may be best known for his discovery of P-22, Los Angeles’ famous mountain lion, in 2012. At the time of the discovery, Ordeñana was studying Griffith Park to learn how the park is connected to the rest of the city and how mammals travelled through it. He had several motion-activated cameras installed to capture the activity of urban carnivores, such as coyotes. Ordeñana noted that spotting the mountain lion for the first time was like seeing bigfoot! This sighting indicated that the animal had likely crossed freeways and even traveled through residential areas to get to the park. Today, the National Parks Service is tracking more than 100 mountain lions throughout Southern California.

In addition to his work studying pumas, Ordeñana also contributes to local and international conservation research, including a jaguar project in Nicaragua, where his family is from, and urban bat research in L.A. He also serves as a member of the board of the National Wildlife Federation, partnering on many of their wildlife conservation efforts. Through his work, Ordeñana hopes to inspire a diverse generation of future wildlife conservationists and educators while increasing accessibility of museums to people of all backgrounds.

Photo of Miguel Ordeñana, courtesy of Natural History Museum of Los Angeles.

By Erica Rymer, PR Coordinator. Published September 30, 2022.